Introduction

I am a web developer, and my work is closely related to the Internet. However, even I sometimes don’t understand how some things work on this very Internet. In this article we will try to figure out what it is and how it works. Let’s start with what the Internet is for us as users.

- What is the Internet?

- Internet at our home

- Internet in a cabinet

- Internet in another cabinet

- Provider hierarchy

- The Internet backbone

- Connecting everything

What is the Internet?

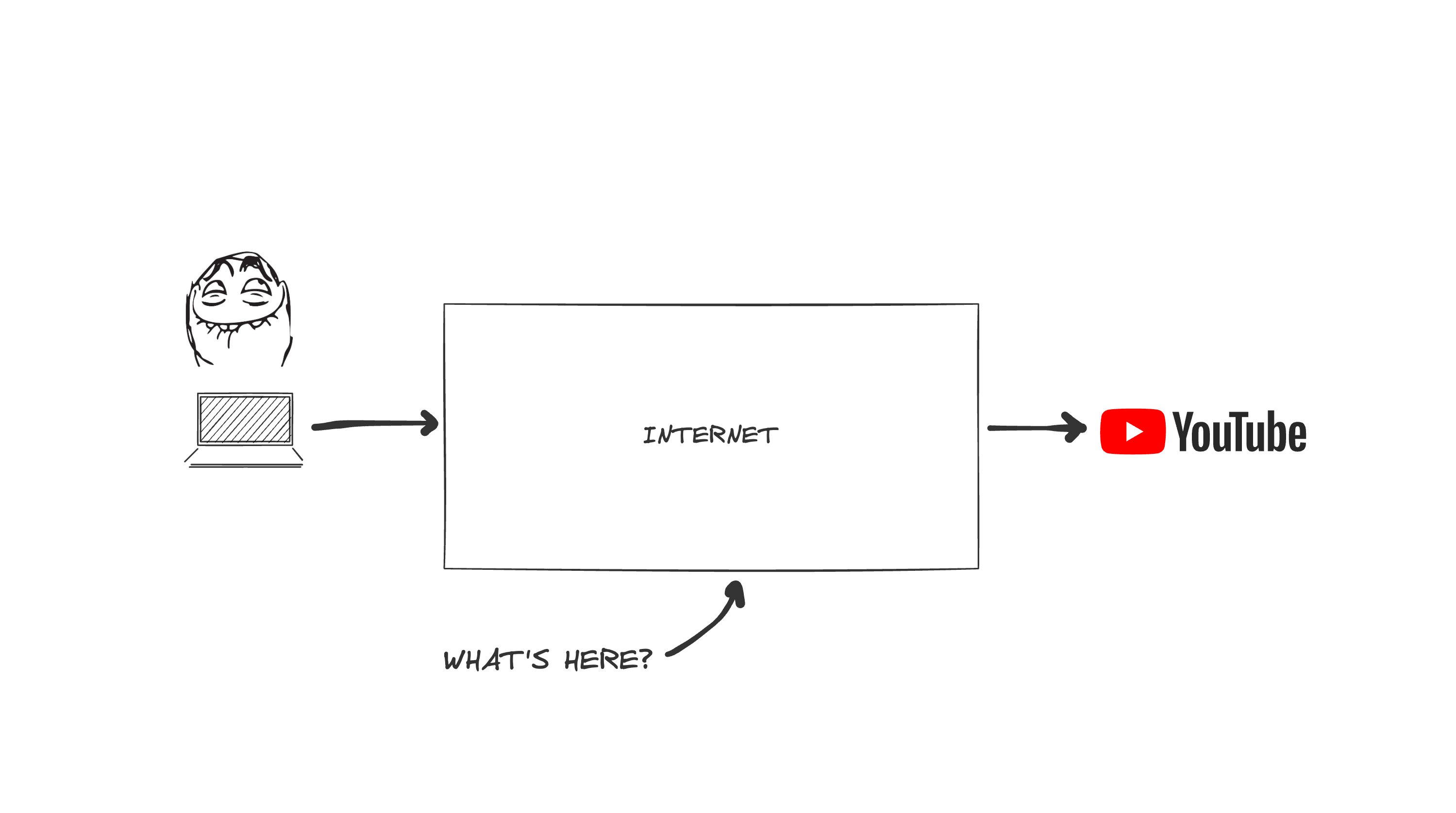

For us, as users, the Internet is a box, a white rectangle with the text that says “Internet”.

There are a lot of interesting things inside this rectangle — like memes, cat videos and other less important information. And all of us somehow connect to this rectangle and go, for example, to `youtube.com`` to watch some videos. (I don’t know about you, but I always connect to YouTube with exactly this expression on my face).

We use the Internet for many hours every day. According to statistics, the average Internet user spends more than 6 hours a day online [ source ]. However, we usually know very little about the Internet and rarely think what it takes for us to be able to watch videos on YouTube any time we want. This article is my attempt to figure out what is inside this white rectangle named ‘Internet’.

Part 1 (Hardware-ish)

First, let’s figure out how the Internet works at a purely physical level, or “what each cable goes where”. To do this, let us think back to how we usually connect to the Internet at home.

Internet at our home

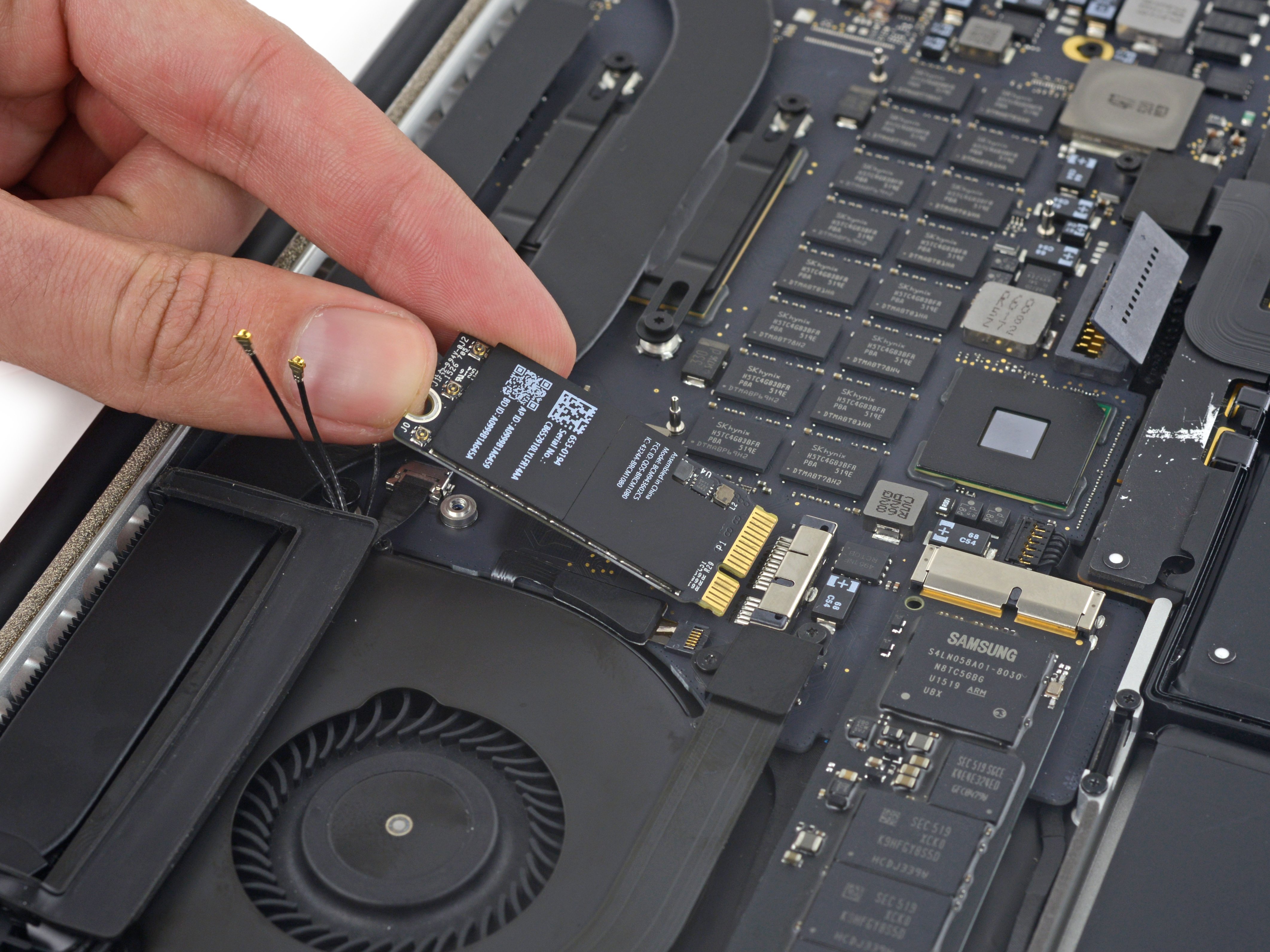

At home, we always connect to the Internet with some kind of device - a physical thing - a computer, laptop, smartphone. Everything that is sometimes more generally called “hardware”. Inside our hardware there is usually a special chip (or a part of a circuit board), which is called a network card. The network card is responsible for connecting to networks. Network cards come in thousands of different types, and they can connect to the network through some king of wires or wirelessly. Nowadays, it is often a wireless connection via the WiFi. Here is, for example, a network card, or rather a wireless module, in an Apple laptop. [source]

Wireless module from MacBook Pro 2015

This wireless module can exchange radio signals with other devices, and if these signals are send and received in specific order it is called “connecting to WiFi”.

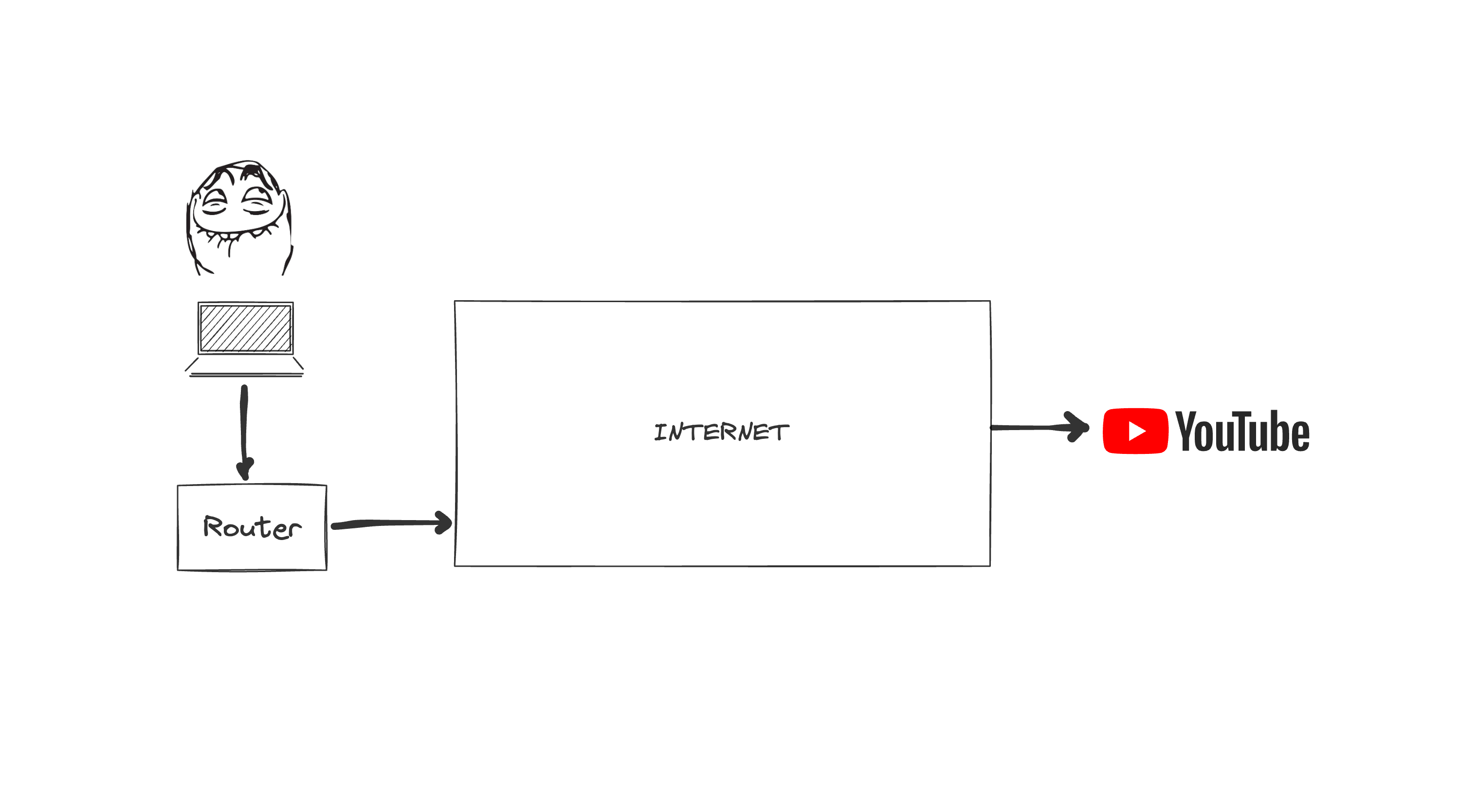

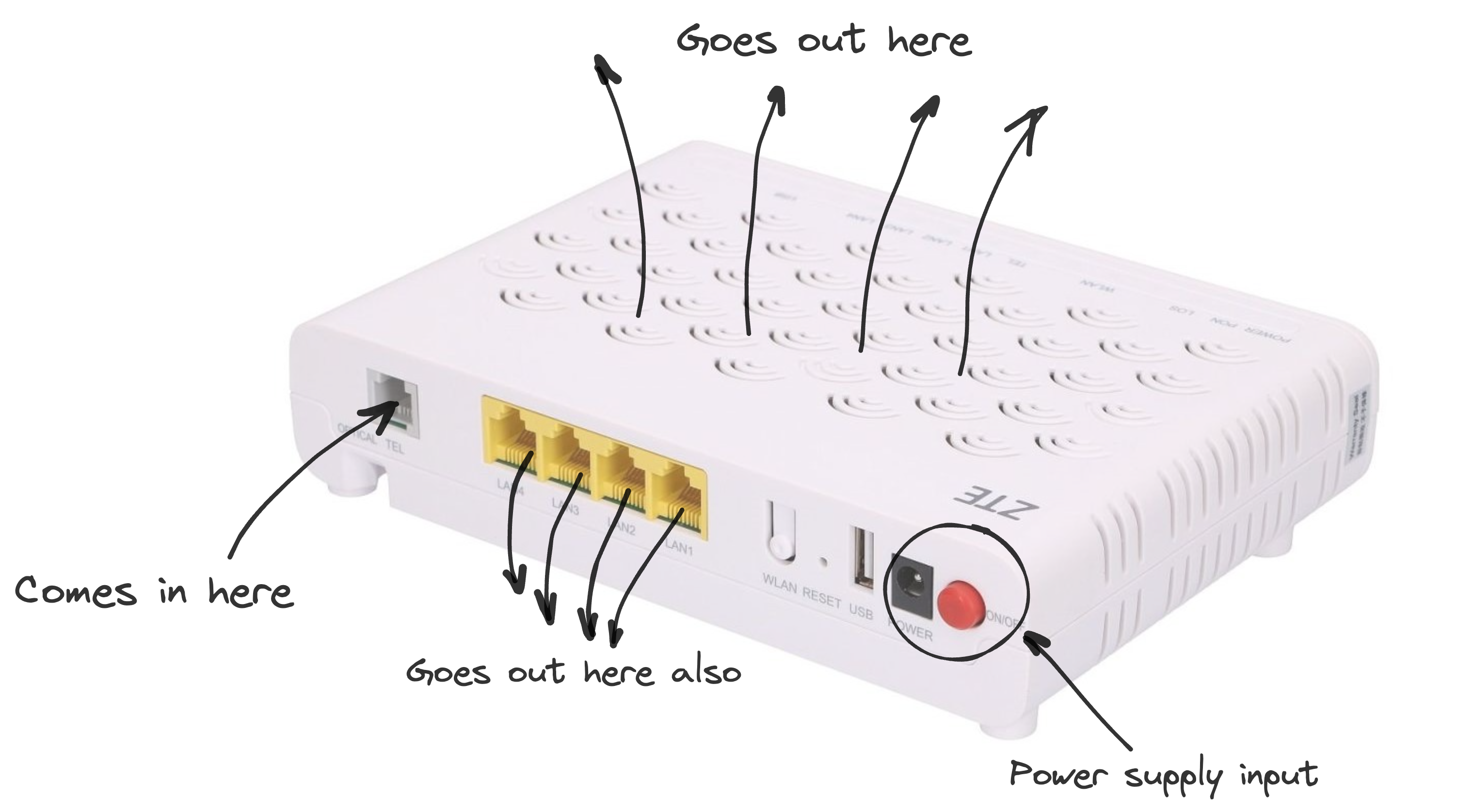

The device to which our network card connects is usually a router. The router looks something like this:

This is a special kind of device with the Internet coming in at one side and coming out from the other side. The Internet comes in from your Internet Service Provider (or ISP) and comes out to clients (or devices) connected to this router via cable or WiFi — laptops, tablets, PCs, gaming consoles, etc.

Basically, for us as users, the process of connecting to the Internet ends here. The very last thing we can see is the internet provider’s cable going through the wall and out of our apartment or house. Let’s follow this cable to see what’s on the other end of it and where the Internet comes from.

Internet in a cabinet

If you live in an apartment building, like me, then you most likely have a cabinet with a lot of wires somewhere in your building or building section. In the best case, this cabinet looks something like these photos.

But it can also look like this.

It all depends on your Internet provider and the specialists who did network cabling in your building.

Regardless of what they look like these cabinets contain routers owned by your ISP. There are so many wires because connections come here from all the apartments in the building. You can plug in from 8 to 48 cables into one router. Therefore, if there are many apartments in the building, then you need several routers, and it is convenient to install them all in one cabinet.

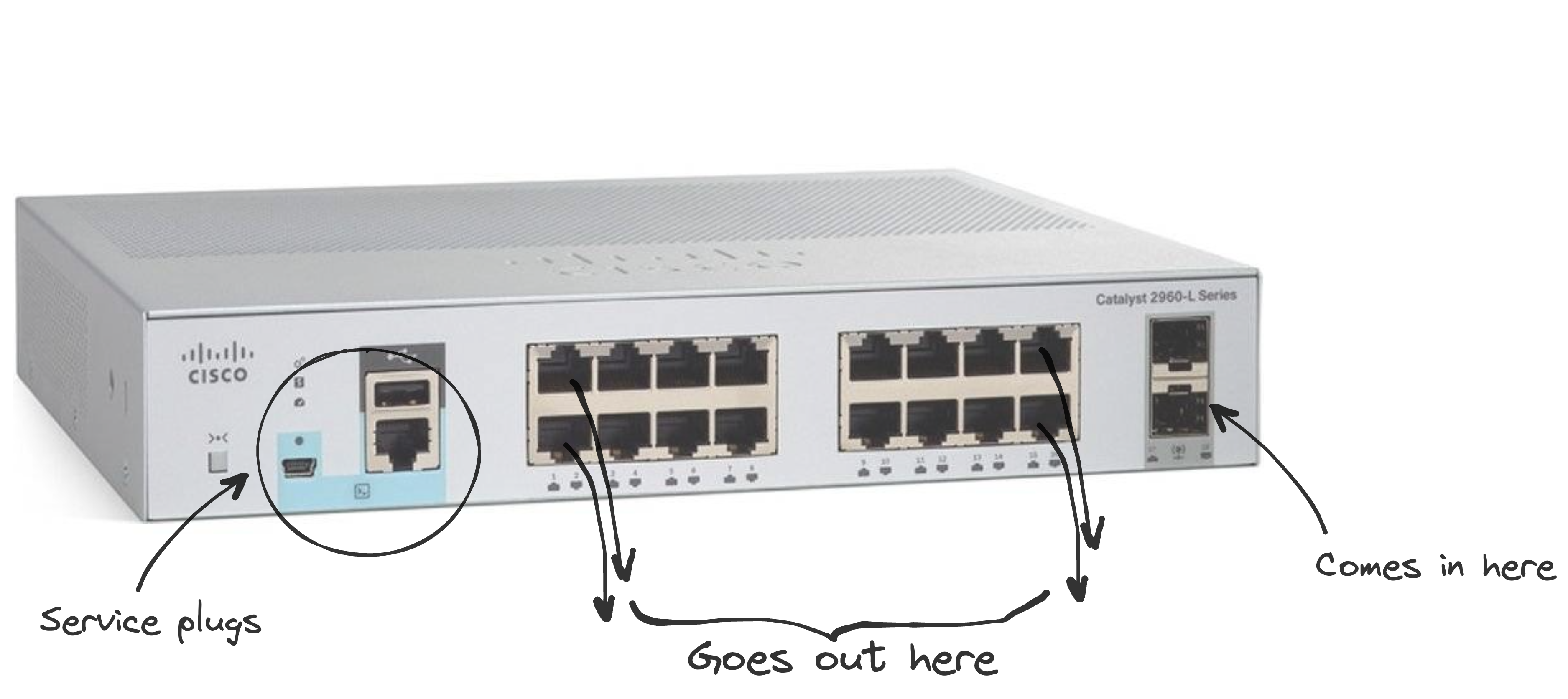

Router from an apartment building cabinet

Routers in these cabinets certainly look more professional than our home routers, but they do the same thing in general. They have the Internet coming in from one side and going out from the other, distributing it to clients. The clients for these routers are all the home routers in all of the apartments in the building.

Of course, there are a lot of differences between routers in the cabinets and home routers, but for now this is not very important to us. For now, we need to figure out where the Internet is coming from to these cabinets of routers.

Internet in another cabinet

The cabinets inside different buildings in a city connect to the Internet via a cable, most often fiber optic. This cable runs to the Internet provider’s data center, where it is plugged into yet another router (it’s routers all the way down!).

Yet another router cabinet

One Internet Service Provider usually provides the Internet to a lot of buildings. So an ISP needs a lot of routers to operate this many connections. And these routers are also arranged into cabinets. Only these cabinets are located in special rooms in special buildings called Data Centers, which are specifically built to operate a lot of network hardware (as well as other hardware like servers). And the cables coming into the routers inside these cabinets no longer connect single apartments but entire buildings. For example, each yellow fiber optic cable in the picture above connects one apartment building.

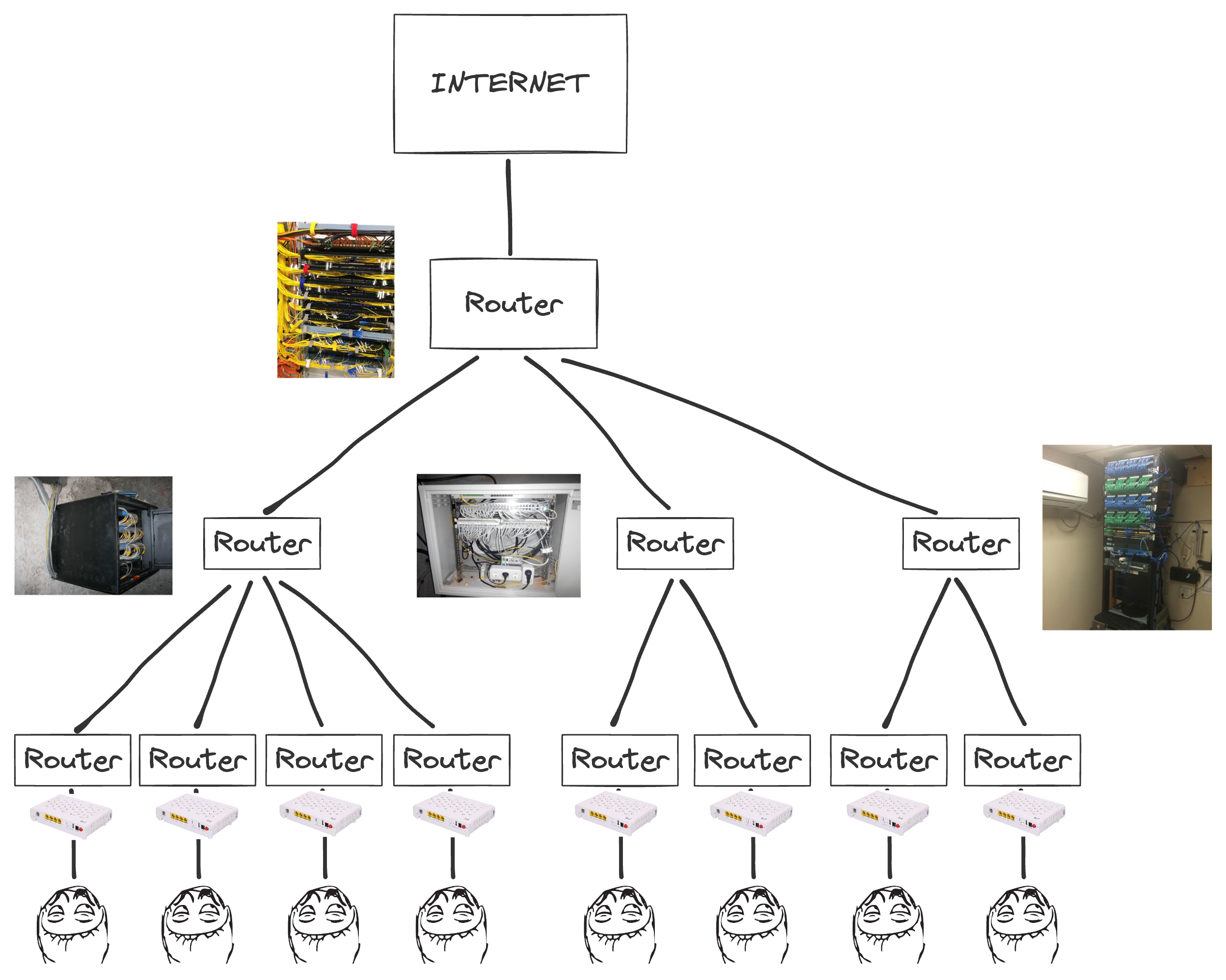

OK, so far we were able to track down the Internet to ISP level with ISP’s network looking roughly as this:

- each client has a router in their apartment

- this router connects to another router installed in a cabinet somewhere in the building

- the cabinet in the building is connected to an even cooler router in the Internet provider’s data center

The ISP needs this system to distribute and manage client access to the Internet. But the provider does not ‘own’ the Internet it distributes to clients. So does the provider get this Internet from somewhere else? Where is the provider’s traffic coming from?

Provider hierarchy

The ISP receives traffic from other ISPs. The Internet itself is all of ISPs and the traffic between them. If we take any two ISPs, then there are three options for interaction between them:

- The ISPs are not connected with each other

- One ISP sells traffic to another

- ISPs exchange traffic with each other (this is also called peering)

Well, the first point is easy to understand. The points 2 and 3, however, are the basis for hierarchy of ISPs. This hierarchy is more of a conventional one, but nonetheless it is used quite often. There are Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3 internet providers.

Tier 3 providers have access to the Internet only through purchasing traffic from higher-tier providers.

Tier 2 providers have access to part of the Internet through exchanging traffic with other providers and purchase access to the rest of the network from other providers.

Tier 1 providers do not pay anyone for the traffic. They only exchange traffic with each other and sell the traffic to lower-tier providers.

There are about 10-15 Tier 1 providers in the world, each of them having access to the entire Internet. Tier 1 providers have the ability to transmit traffic between different countries and continents, and they are able to do this because they own or lease the Internet backbone.

The Internet backbone

The Internet backbone cables (also known as backbone networks) physically connect parts of the Internet located in different countries and on different continents. The map of backbone networks looks roughly like this. [Infrapedia]

Internet backbone map

I used the word “roughly” because no one knows exactly what they look like. There is no central repository of information about all backbone cables. The backbone network allows traffic to be transmitted around the world. For example, if you sit in your home in Europe and want to open a website located on a server in the USA, then your traffic will go through the backbone network. To be more specific, your traffic will go through one of the backbone cables laid along the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

Intercontinental submarine cables

And this is what submarine cables look like. [ Wired article ] They have several different layers of protection with fiber optic inside. The throughput of modern cables reaches in tens of Tbit/s. Backbone cables not only run along the ocean floor, there are also land-based backbone networks. For example, in Europe the backbone cable network looks like this. [source]

Internet backbone map of Europe

These networks are operated by major Internet providers — Tier 1 providers or regional Tier 1 providers. Regional Tier 1 providers are providers that are not Tier 1 at the global level because they still buy transit traffic, but they do not pay for the traffic inside their region.

Okay, we now understand a little bit more about backbone networks. Now let’s go back to the beginning of our journey and try to connect together everything that we have learned so far.

Connecting everything

Let us sum up what we have learned.

We learned about the structure of an ISP network - each client has a router at home. This router is connected to the cabinet with routers inside the building. The cabinets in the buildings are connected to the router in the Data Center.

ISPs come in different levels. They buy, sell and exchange traffic.

The largest Tier 1 providers transmit traffic between countries and continents using backbone networks, with traffic sometimes running through cables at the bottom of the ocean.

So where does the Internet ultimately come from? Where is its “source”? That is the whole point — it is nowhere. There is no Internet source where the Internet is produced and then sent out to consumers. Asking where is the source of the Internet is like asking where is the source of mail or telephone communications. The Internet is a set of devices that want to communicate with each other, a huge infrastructure for providing communication and a large set of technologies that allow this infrastructure to operate.

To understand how big and complex the Internet is, let us go back to our ISP network diagram. There were only 8 clients there. In reality, each provider has from several thousand to tens of millions clients. And there are tens of thousands of providers all over the world. And not only you and I need the Internet in our houses and apartments. Companies and organizations also need it. Large IT companies very often build entire separate data centers just for themselves, and they also need the Internet. And we haven’t even started with IoT. As a result, it all connects into a huge network that covers the entire planet.

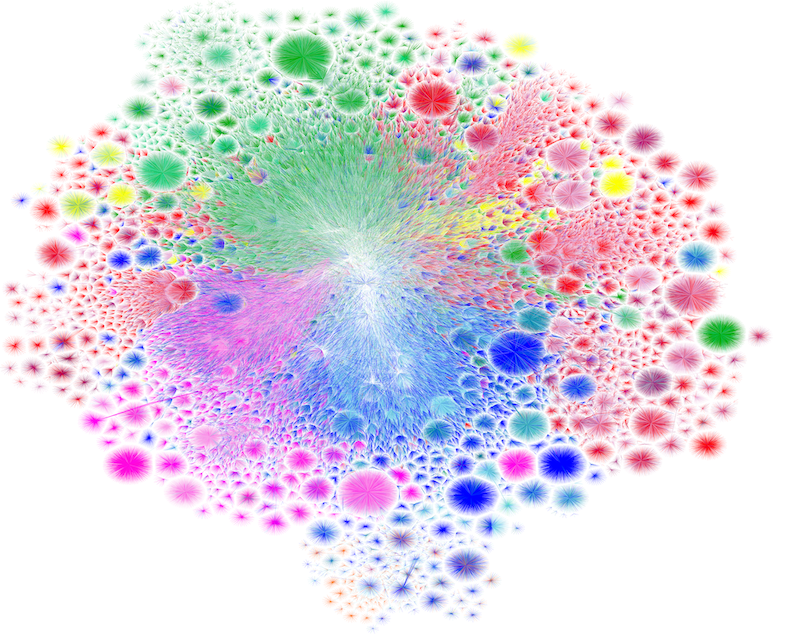

The Internet map from The Opte Project

And there are more than 28,000,000,000 devices online in this giant network, and this number continues to grow.

So, 28 billion devices is certainly a mind blowing number, but how do we find, for example, YouTube among all these devices?

We will try to figure this out in the second part.