Introduction

In the first part, we looked at what the Internet is in terms of cables, routers, and other infrastructure. We looked at who owns this infrastructure and how it connects 28 billion different devices into one giant network.

In Part 2, we will try to understand what people have come up with on top of this infrastructure so it is possible to find things on the network.

- Name, address and route

- Where is it located

- A little history

- What to do

- Private networks

- Shared hosting

- What are we looking for

- Route or how to get there

- Divide the Internet

- Border Gateway Protocol (BGP)

- Everything together

Name, address and route

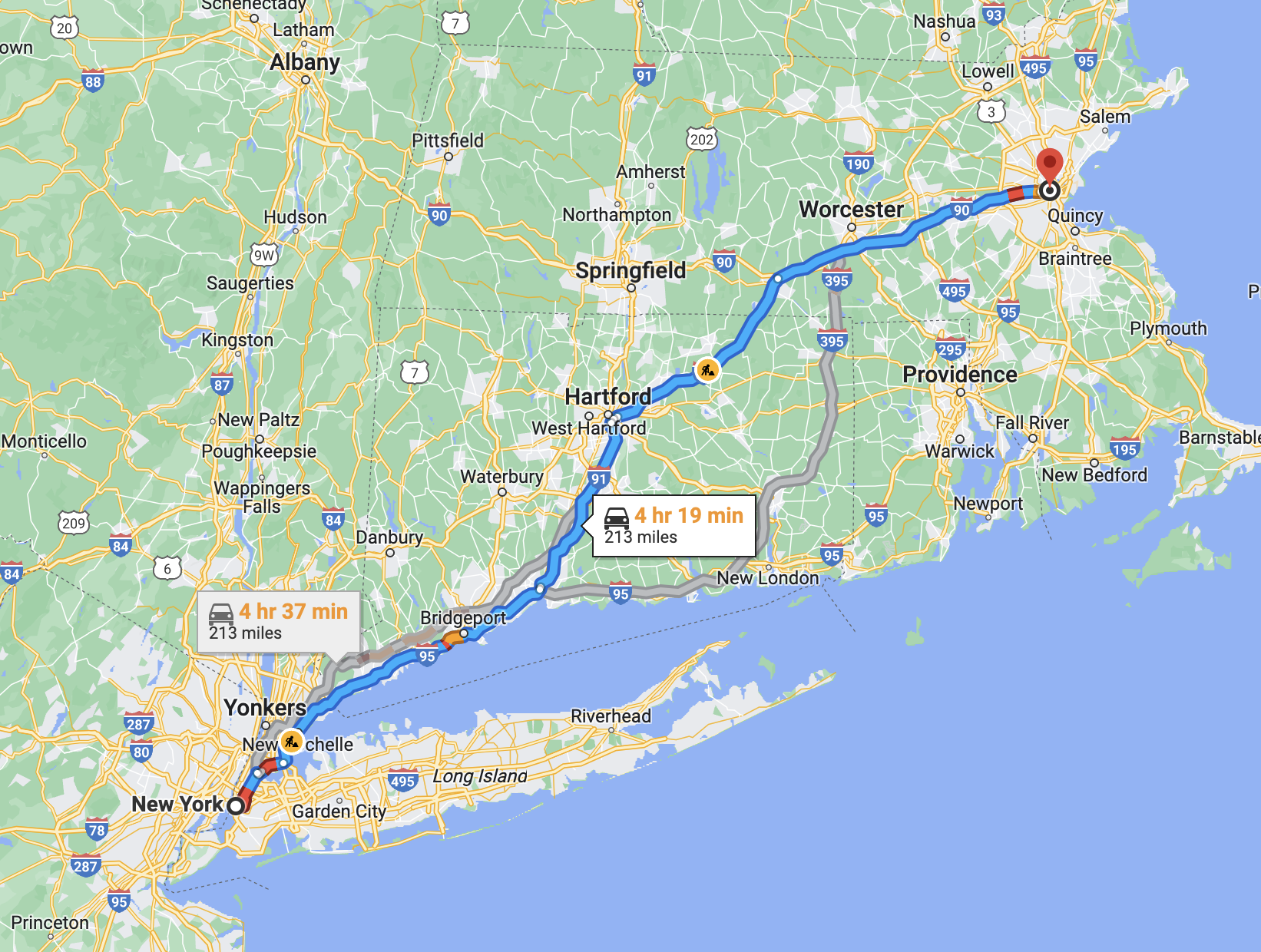

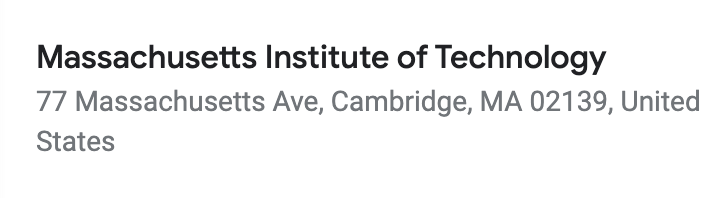

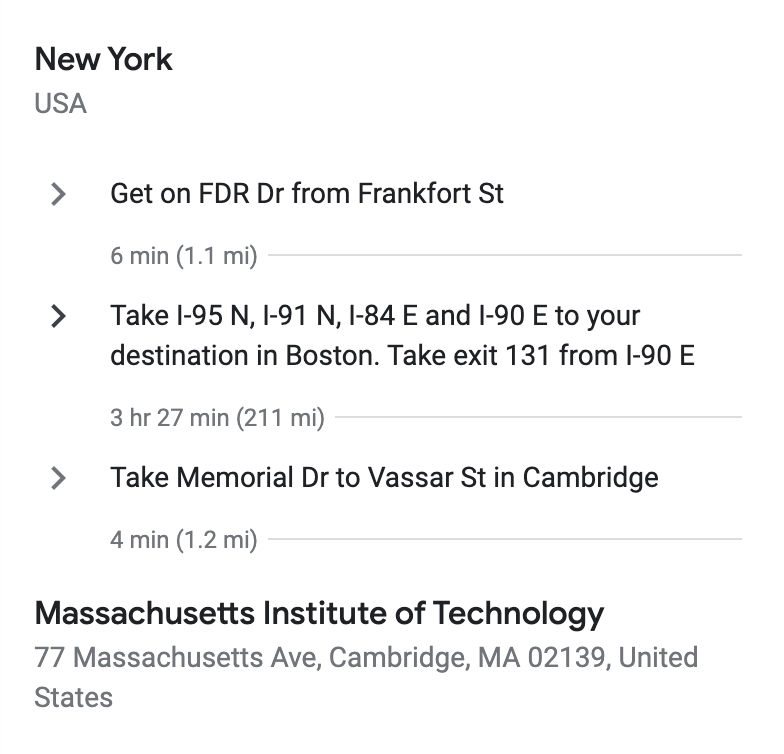

First, let us think a little bit about how we find places in our familiar physicall world. Usually, it all starts with us knowing at least the name of the place where we want to go. Suppose I want to go from New York to Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston by car.

To get to MIT, I need first to find out its address. Quick search gives me the following address:

This address contains everything I need to know to identify a place — country, city, street, and a house number. All this information uniquely determines the place I need. If we change something in the address, it will be a different place (or even a non-existent one). For example, suppose we change the house number in the MIT address to 190. Then the address will change to 190 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge. This will not be MIT but Flour Bakery + Cafe. It is still in Cambridge and not that far from MIT, but it is a different place. If we change the name of the street - for example, to Mt. Auburn Street - we will get 70 Mt Auburn St. This is still in the same city, but already pretty far from MIT, like a half-hour walk. And so on, if we change city or country in the address, then chances are there will be no such place at all. 77 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, France — a place with this address does not exist.

All this show that a set of country, city, street and house number gives us a unique combination that indicates the building we need. In other words, each address corresponds to one specific building or place, and each place has one specific address.

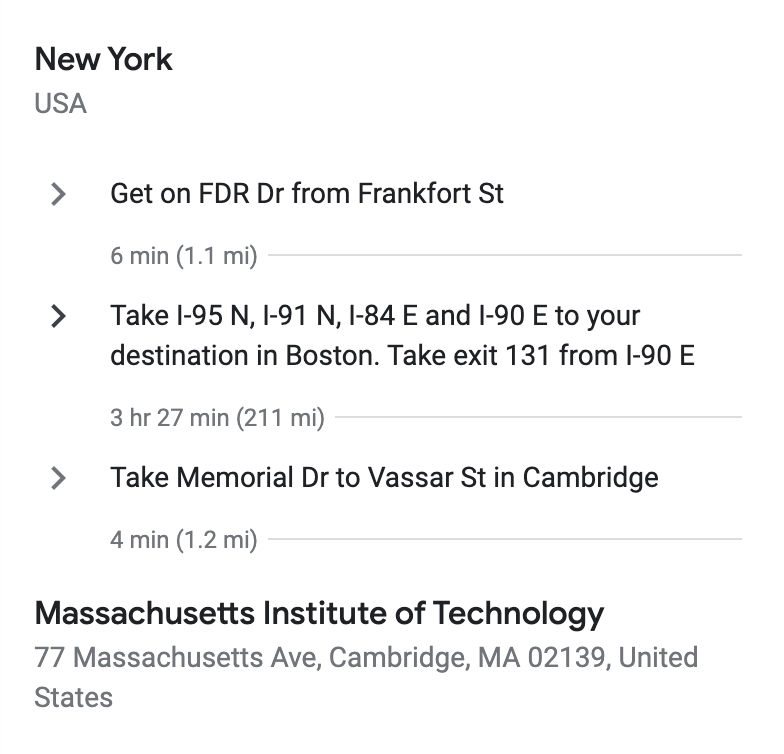

To get to the right address, you need one more thing - a route. A route is a sequential set of points you need to pass through to get to your destination. For example, Google Maps gives the following route from New York to MIT:

To sum up, for orientation in the physical world it is necessary to know three things:

Name - What are we looking for

Address - Where is it located

Route - How to get there

The same concepts apply to the Internet, and there is a protocol for each of them:

Name - Domain Name System (DNS)

Address - Internet Protocol (IP)

Route - Border Gateway Protocol (BGP)

First, let’s figure out how Internet addresses work.

Where is it located

We have a good idea of how an address works in our physical world. If YouTube were a physical place where you come and watch videos, then its address would probably look something like this:

But YouTube is NOT a physical place. It is a video hosting resource on the Internet. So its address looks like this:

This is an IP address. IP is an abbreviation of the name of the protocol that is responsible for addressing on the Internet. The name itself is not very creative. It is called Internet Protocol.

People from the tech industry encounter IP addresses quite often and so these addresses may seem quite familiar. But someone looking at IP addresses for the first time may have many questions:

- What do all these numbers mean?

- And why are there numbers here anyway?

- Why can’t we write this addresses in more understandable way?

- How can you even figure out where the place is from this address?

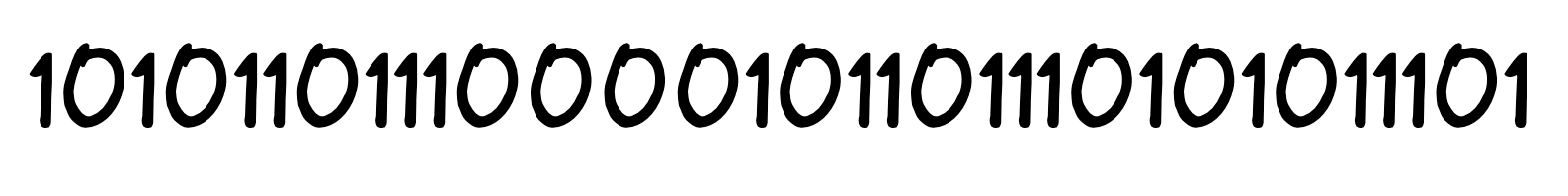

In fact, this address is very clear. It’s just that it is clear to a computer, not to a person. An IP address is needed so that computers can find each other on the vast Internet. And so IP addresses must be well understood primarily by computers, and people have to adapt. Even writing an IP address fomatted as four groups of three digits (as above) is a very “humanized” notation. Inside the computer the address looks like this:

Computers generally only understand bits and the binary number system, so each IP address is a set of 32 zeros and ones. For us people, it is split into four parts and then translated into the decimal system familiar to us. It is still not very convenient, but working with four decimal numbers is still much easier than remembering 32 zeros and ones every time.

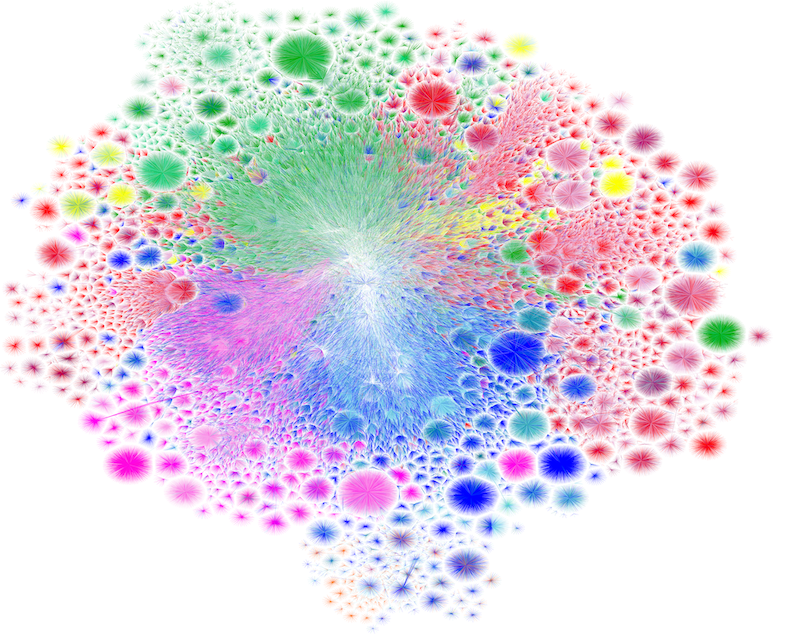

By the way, since an IP address consists of 32 zeros and ones, there can be a total of 4.3 billion unique IP addresses. At the same time, at the very end of Part 1 there was a beautiful picture with a visualization of the Internet. We talked about how the Internet has 28 billion devices connected to it. But how is this possible? There are 28 billion devices, but only 4 billion addresses? After all, every device on the network should have a unique address so that others can find it. Or maybe not?

To understand how this is possible and how the Internet still continues to work, although there are 7 times more devices than unique addresses, we need to delve a little into history.

A little history

The Internet dates back to the Cold War, when researchers at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) of the US Department of Defense created the first networks. The researchers wanted to create a communications system that would continue to function even when much of the system was destroyed, for example, as a result of a nuclear strikes.

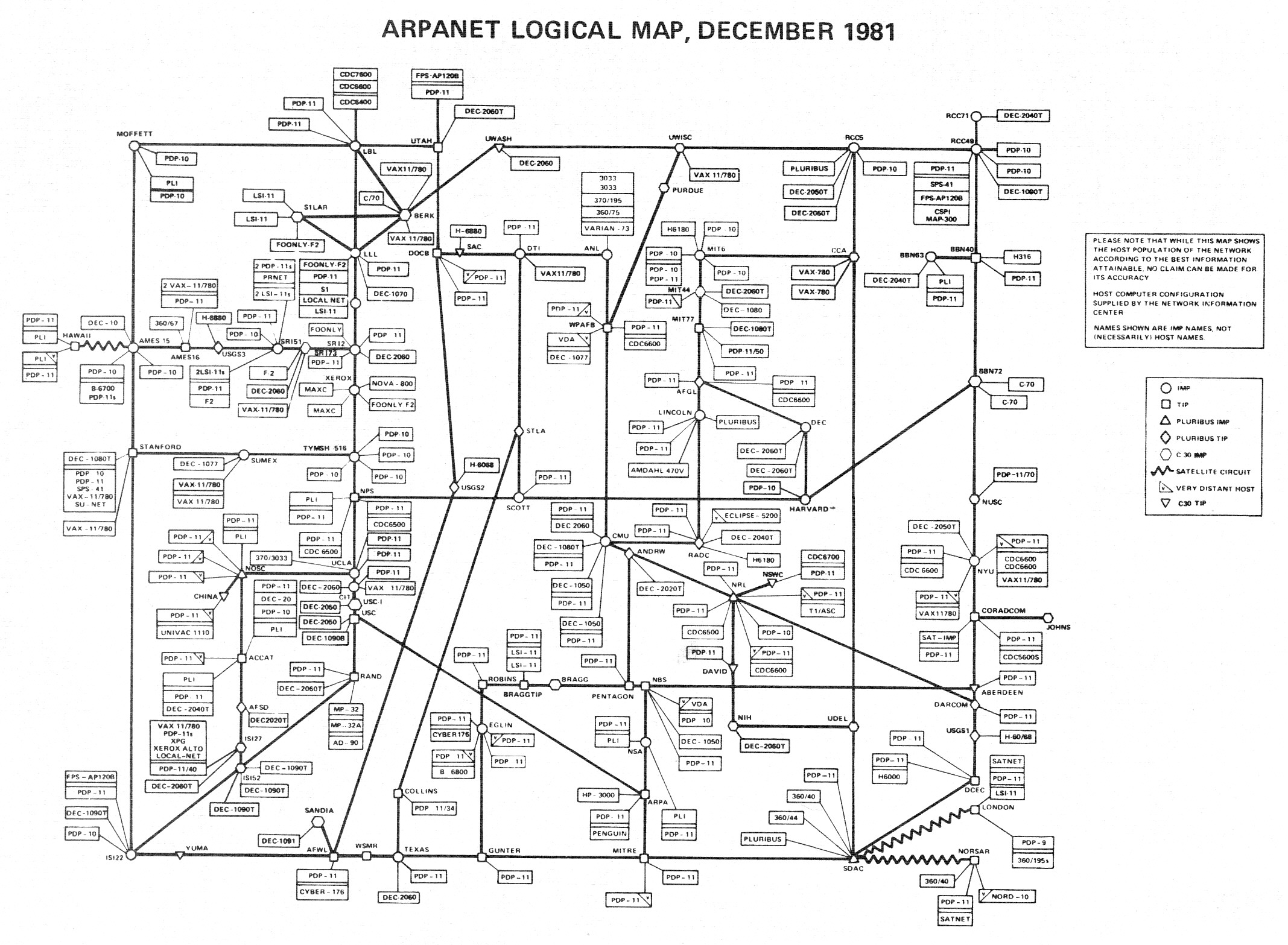

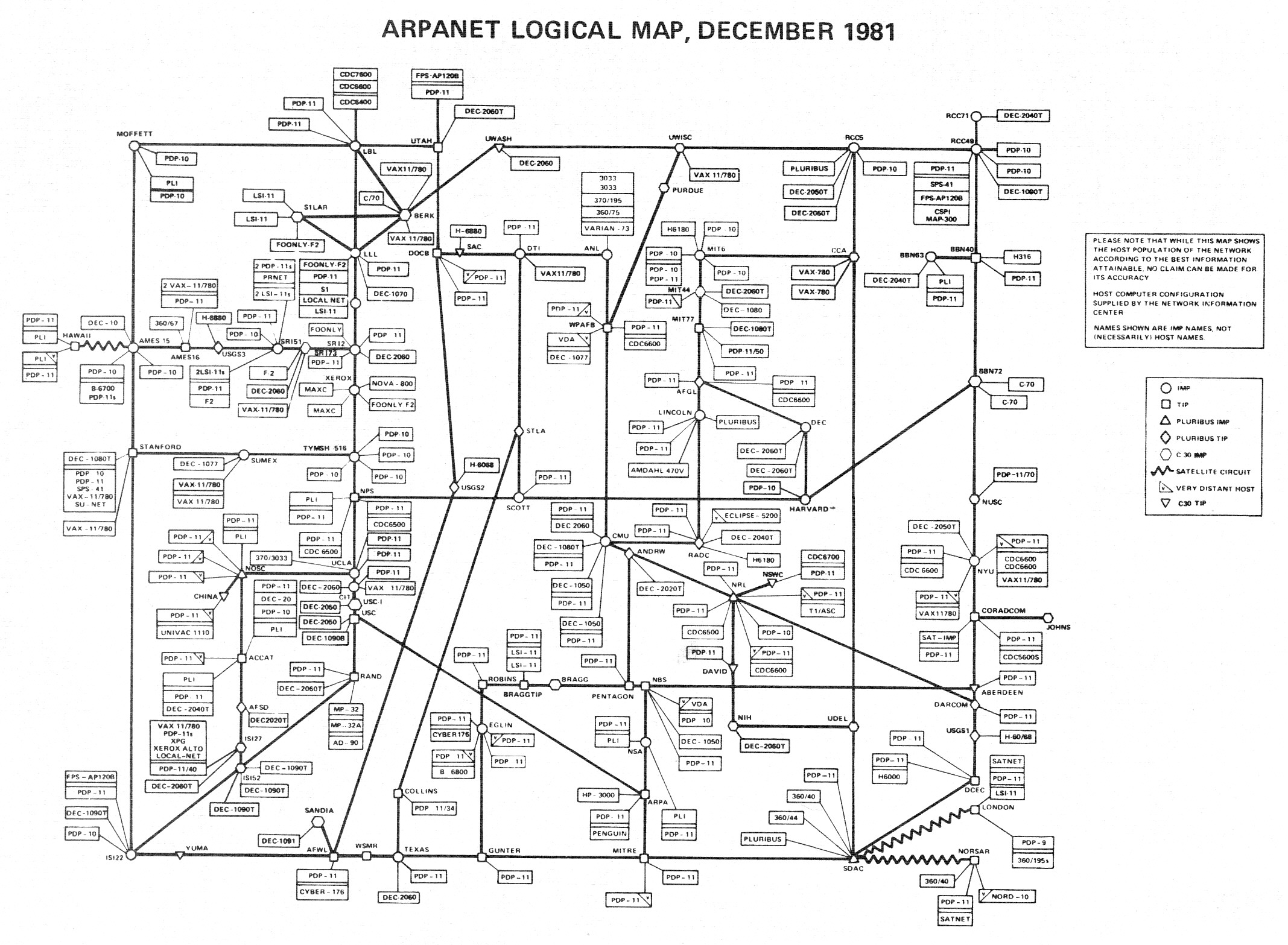

One of these systems, which eventually formed much of the basis of the Internet, was called ARPANET. It was created at the end of 1969 and existed until 1990.

This diagram shows the ARPANET in 1981, around the time of the IP protocol creation [ source ]. Once again, the ARPANET was the largest network at the time, and this diagram shows ALL the nodes in the network — a little more than 200 computers. Of course, when you come up with addresses for networks and the largest network at that time has 200 computers, then 4.3 billion seems to be sufficient number of addresses with a huge margin.

It is also important to remember that ARPANET was developed for the milirary applications, and, of course, was not intended for widespread use. Even ARPANET’s successor NSFNET, which included many more nodes, could not even come close to running out of IP addresses.

When the IP protocol was created, no one imagined that computer networks would eventually grow into the global Internet and that they would grow so quickly.

So here’s a meme, which shows well what people thought (as I imagine it) about the number of addresses on the Internet when they came up with IP.

This is a kind of meme that may require some explanation (not the best kind of memes, I know). IP originally envisioned three classes of networks. Now, it does not matter what these three classes are, we just need to look at the scale in terms of number of nodes. In short, the IP initially envisioned three types of networks — the smallest ones (class C) with a maximum of 254 nodes, the larger ones (class B) with up to 65,534 nodes, and the SUPER HUGE ones (class A) with almost 17 million.

Therefore, when we talk about why IP addresses were created the way they were, we need to remember that at the time, people probably thought they had come up with ALL the addresses that humanity would ever need. At the time, no one expected we will run out of the IP addresses within 30 years.

However, after 30 year, we ran out of the IP addresses, and this problem had to be solved somehow.

What to do

People realized there was a problem quite early on. Already in the 1990s, a new standard for Internet addresses was developed. This is also the same IP protocol, but version 6. This version supports an unimaginably large number of addresses - 3.4 × 10³⁸.

It is 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times more than the IPv4 currently in use.

The adoption of IPv6 is taking place throughout the Internet, but, unfortunately, it is going very slowly. Currently, about a third of devices on the Internet use IPv6.

But, of course, IPv6 alone would not be enough to solve the address problem because a complete transition to IPv6 requires every device on the Internet to switch to using IPv6. It was clear from the start that this was going to be a very long process. And also, the IPv4 addresses began to run out already in the early 2010s, when IPv6 was just beginning to be adopted.

IPv6 is necessary to increase the available pool of addresses. But, besides this, we can also come up with different ways to use existing address pool more efficiently.

Private networks

One way is to use one IP address for many devices. This can be done using private networks.

Suppose we have a router with 4 devices connected to it. The router has a public IP address visible to the entire Internet. But between the router and the devices we can set up an internal (or private) network with its own set of IP addresses, which are not visible to the rest of the Internet.

Since this is an internal network, not accessible to other devices on the Internet, you can use any of the 4 billion addresses inside this networj and there will be no problems. Whatever addresses we use on the internal network, for the rest of the Internet our 4 devices will have the same public address, and thus we won’t “waste” for separate IP addresses for our four devices.

Shared hosting

Another way to reduce the need for IP addresses is shared hosting.

Suppose we have 4 different websites. We can host these websites on one server, and they all will have the same IP address. The server itself will figure out when to show which site. The important thing is that we don’t need a separate IP address for each site.

All these methods help to manage 4 billion IPv4 addresses so far. The problem will finally be solved when most of the Internet switches to IPv6, but for now - private addresses for everyone!

What are we looking for

So, we’ve figured out the Internet addresses. But how can I find the address for the website I need to open?

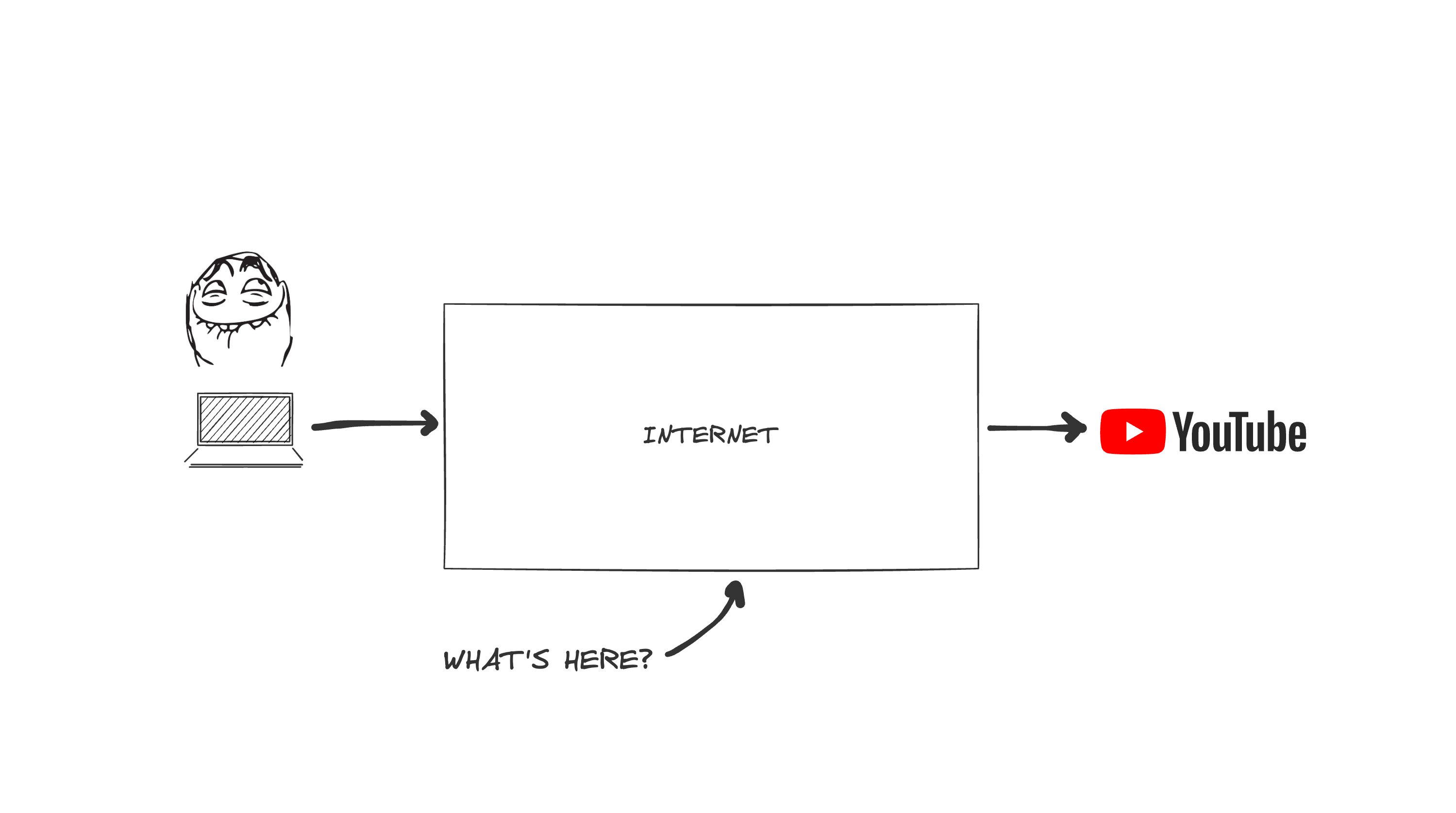

Remember we had this picture at the beginning? There is a user who wants to go to the YouTube to watch videos. How do users do that?

One way could be like this — a user goes to the browser, types “youtube.com” in the address bar and presses Enter. Then a short time passes and YouTube opens.

And here’s the question. As we remember, computers on the Internet use IP addresses. And if the browser was able to open YouTube, it means our computer somehow converted “youtube.com” into an IP address, found it on the network and downloaded the necessary data. How did it do it?

There is a whole special system for this on the Internet. It is called Domain Name System - or DNS for short.

This system works as the Internet phone book or a contact list in the smartphone. All these three things — DNS, phone book, and contact list — have the same idea basic idea: knowing a name of a person or a company, we can find the phone number or address. DNS is essentially a global contact list for the Internet.

If you remember, we had this picture a little bit above. The DNS system is responsible for exactly this kind of configurations — which address corresponds to which domain name. With the help of the DNS you can create different configurations. You can do it like in the picture - when one address corresponds to several names. You can do it the other way around - so that one name corresponds to several addresses. And, of course, simplier options with one address corresponding to one domain.

Route or how to get there

OK, we now understand how addresses on the Internet work and how to convert a name to an address. Great!

Suppose we know the address. How to get to it?

To get to an address in our familiar world of cities, streets and houses, we need to know the sequence: where to go, where to turn, what transport to take at what stop, etc.

For example, as we remember, my route from New York to the MIT looked like this:

It is a set of intermediate locations you need to pass to get to your destination.

What about the Internet? In fact, it is about the same.

Let’s look at a simple case first. Suppose there are only 5 computers in our network, and they all connect to one router. How can we make it so that any computer on the network can connect to any other at its address? In this case, the simplest possible scheme works - each computer tells the router its address, and then the router knows the addresses of all the computers. All routes in this network are very simple. To connect to any address on the network, a computer needs to connect to the router and tell it the address it needs. Then the router itself will connect you to the desired computer.

But what if the network is larger and more complex, for example, like ARPANET?

In fact, the same approach works here as in our five-computer network. Yes, there are far more than five nodes in the ARPANET, and the routes are more complicated, but all the routes can still fit in the memory of one router. And then everything works the same: computers coonect to the router, and the router provides the required route.

And it worked like that for a long time, until the number of addresses on the network began to grow very quickly. At some point, routes no longer fit into memory of even the biggest routers. So it was necessary to come up with something to solve this problem.

Divide the Internet

If we can’t fit all the routes into memory, may be we can somehow fit a part of them and figure out a way to communicate between the parts?

Suppose we split the entire Internet into separate large networks. These large networks will know the routes to each other, but not to each specific node within others networks. Each network will appear as a single entity to the rest of the Internet. These large networks will exchange routing information with each other, and this way every large network will know how to get to any other large network.

These “large networks” of the Internet are called Autonomous Systems (AS). There are special routers at the borders of these systems that exchange routing information with each other. The router at the systems borders are very powerful routers capable of storing several route options for all other autonomous systems and choosing the optimal one.

Divinding the Internet into Autonomous Systems allows us to reduce the task to the already solved one. Since we can store all the routes to all Autonomous Systems in one router, we can apply the same principle as in our simple five-computer network or in ARPANET. In ARPANET, the routers knew the routes to each specific node in the network, but now the routers know the routes to each Autonomous System.

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP)

Autonomous Systems need to know how to get to each other. But the Internet is constantly changing - backbone cables can stop working, the ISPs have accidents, some ISPs may experience increased loads, etc.. Therefore, routes on the Internet are constantly changing. This means that Autonomous Systems must somehow be able to exchange up-to-date information about routes. There is a separate protocol for this - Border Gateway Protocol or BGP.

The BGP protocol allows Autonomous Systems to exchange routes with each other. Route exchange is based on IP address prefixes assigned to each Autonomous System.

For example, Autonomous System 1 (AS1) has addresses that begin with 173.194.221. AS1 informs its neighbors that addresses like 173.194.221.*** are its addresses. And then the neighbors inform their neighbors, etc. After some time, all Autonomous Systems know that if they receive traffic with an address that begins with 173.194.221, then this traffic needs to be directed towards Autonomous System 1.

Autonomous systems are network operators with technical ability to manage a large set of IP addresses — ISPs, networks owned by large companies, universities, etc..

In this diagram, AS1 could be, for example, Google, AS2 could be AT&T, and AS3 could be some small ISP in your city.

BGP is an important protocol. It allows Autonomous Systems to find other Autonomous Systems across the vast Internet. The BGP is crucial for the Internet, and the cost of errors in its configuration is very high. Bugs in BGP can cause entire networks to disappear from the Internet. For example, this happened with Autonomous System of the Facebook in early October 2021. Errors in BGP configuration led to other Autonomous Systems unable to communicate with the Facebook network. As a result, all Facebook services went offline for 6 hours. At the same time, the servers themselves were working and were ready to receive traffic, but no one knew where to send this traffic.

Everything together

So, we learned how the Internet works on the physical level. Then we figured out names, addresses and routes on the Internet. Now let’s try to combine all this into one picture.

Imagine that somewhere on the planet, let’s say in Berlin, there is an internet user sitting at home connected to the network of a Tier 3 regional provider, and this user wants to watch a video on YouTube.

User’s computer is connected to a router, which is connected to the global network through several layers of other routers.

The user types “youtube.com” in the browser search bar. The browser finds the IP adderss for “youtube.com” through the DNS system and sends a request to this address.

The request travels through the provider’s network and goes to Google’s Autonomous System through through Tier 1 ISPs and their backbone cables that transmit traffic to North America.

The request uses the route that was possible to compose thanks to the exchange of information between Autonomous Systems via the BGP protocol.

The request comes to the YouTube server inside the Google Autonomous System. The server responds to the request and the happy user watches his favorite cat videos.